Name no one man

Mystery is a great embarrassment to the modern mind.’

– Flannery O’Connor, ‘The Teaching of Literature, Mystery and Manners, 1957

‘Man's naked form […] belongs to no particular moment in history; it is eternal, and can be looked upon with joy by the people of all ages.’

– Auguste Rodin

It started with a conversation. We spoke about the representation of the male nude in art; the scant examples compared to that of women; the perception that male photographers of recent history have sexualised the male body. It made me wonder: what kind of images I would create when presented with a naked male body? How would my own position affect what I see and what I capture, how that body — that person — reacts towards me?

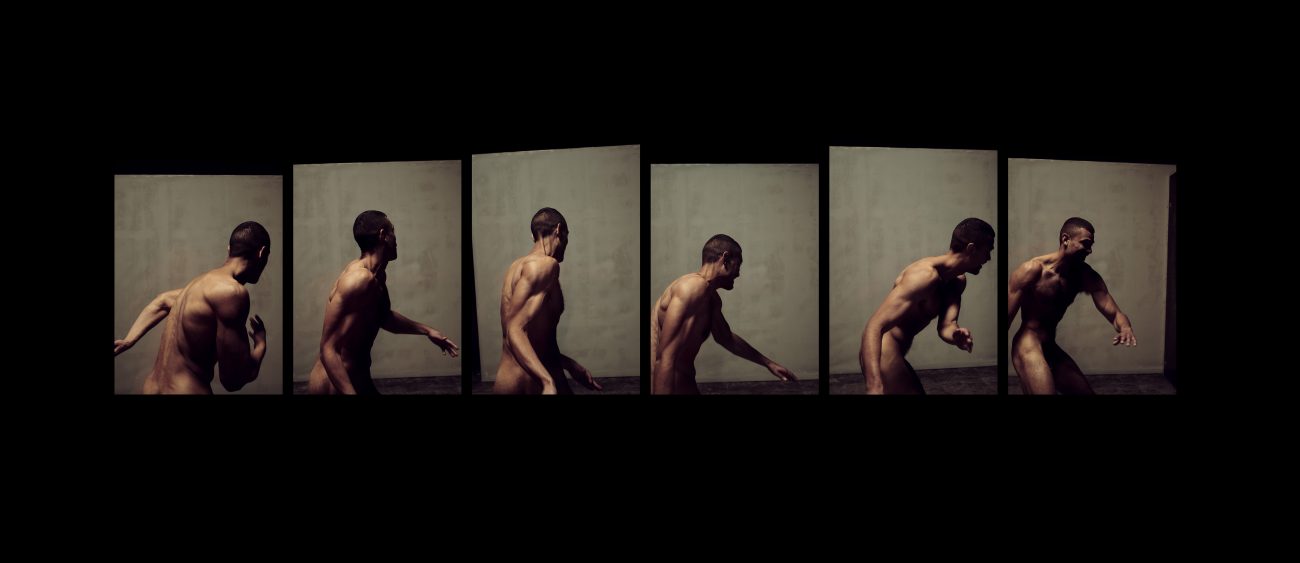

The process was not glamorous (photographic shoots rarely are). I hired a nightclub in London’s once-industrial east end; a space empty all week and full to capacity with bodies all weekend. For a few intense weeks I worked alone with artist models, men who had responded to a call out. I didn’t meet them beforehand; we exchanged just a few perfunctory emails. I wanted to work with artist models because they were accustomed to sitting and holding poses, of course, and the way in which the shoot unfolded became like that of a gesture drawing: the laying in of the action, form and a pose held for as little as ten seconds and as long as five minutes.

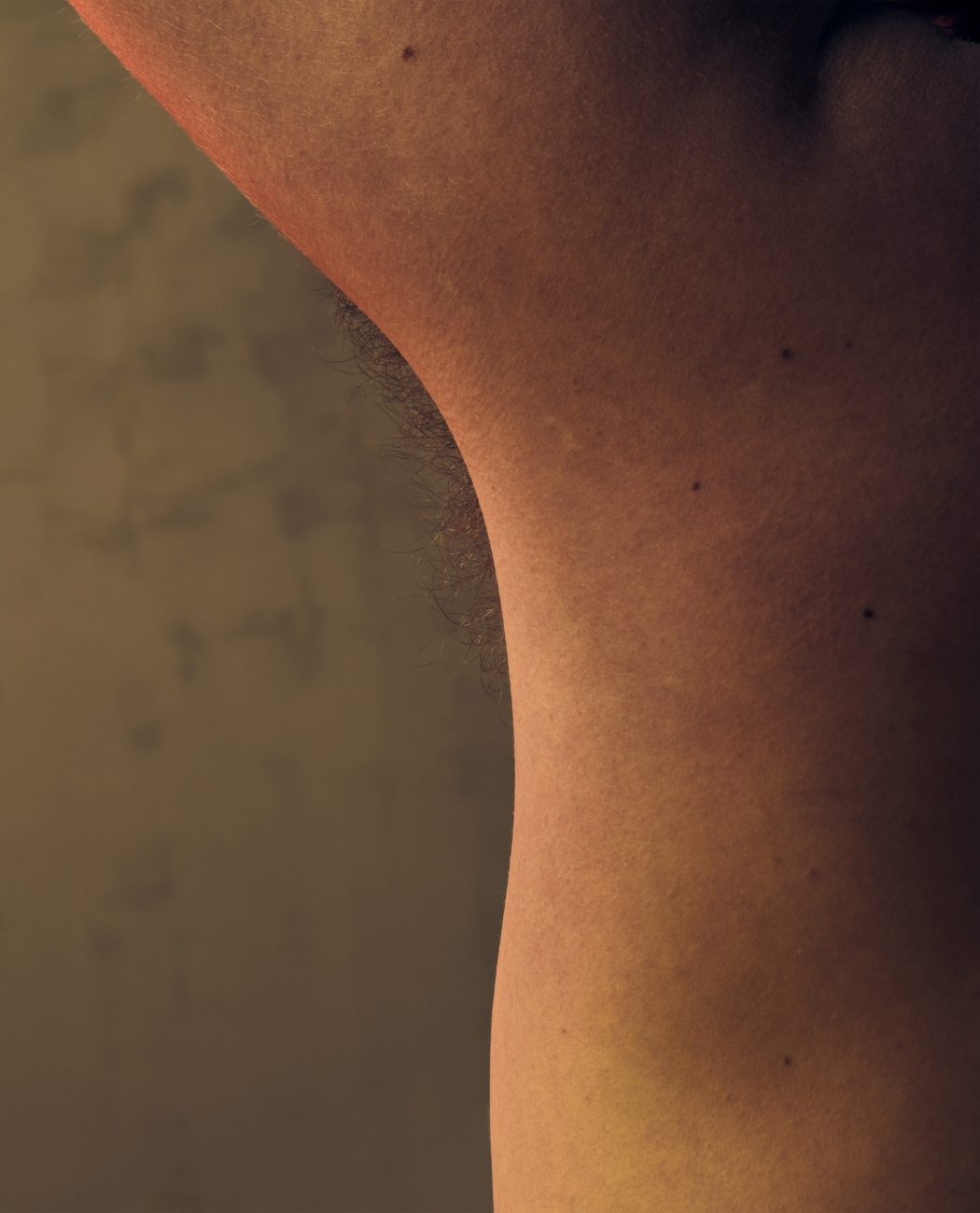

This space allowed me to use light to accentuate form. Light to dark, the full tonal range. The absence of clothing removes any associations with fashion, and therefore with identity. I wondered if reducing the body to a characterless form would make them more relatable to the viewer. Shedding a layer.

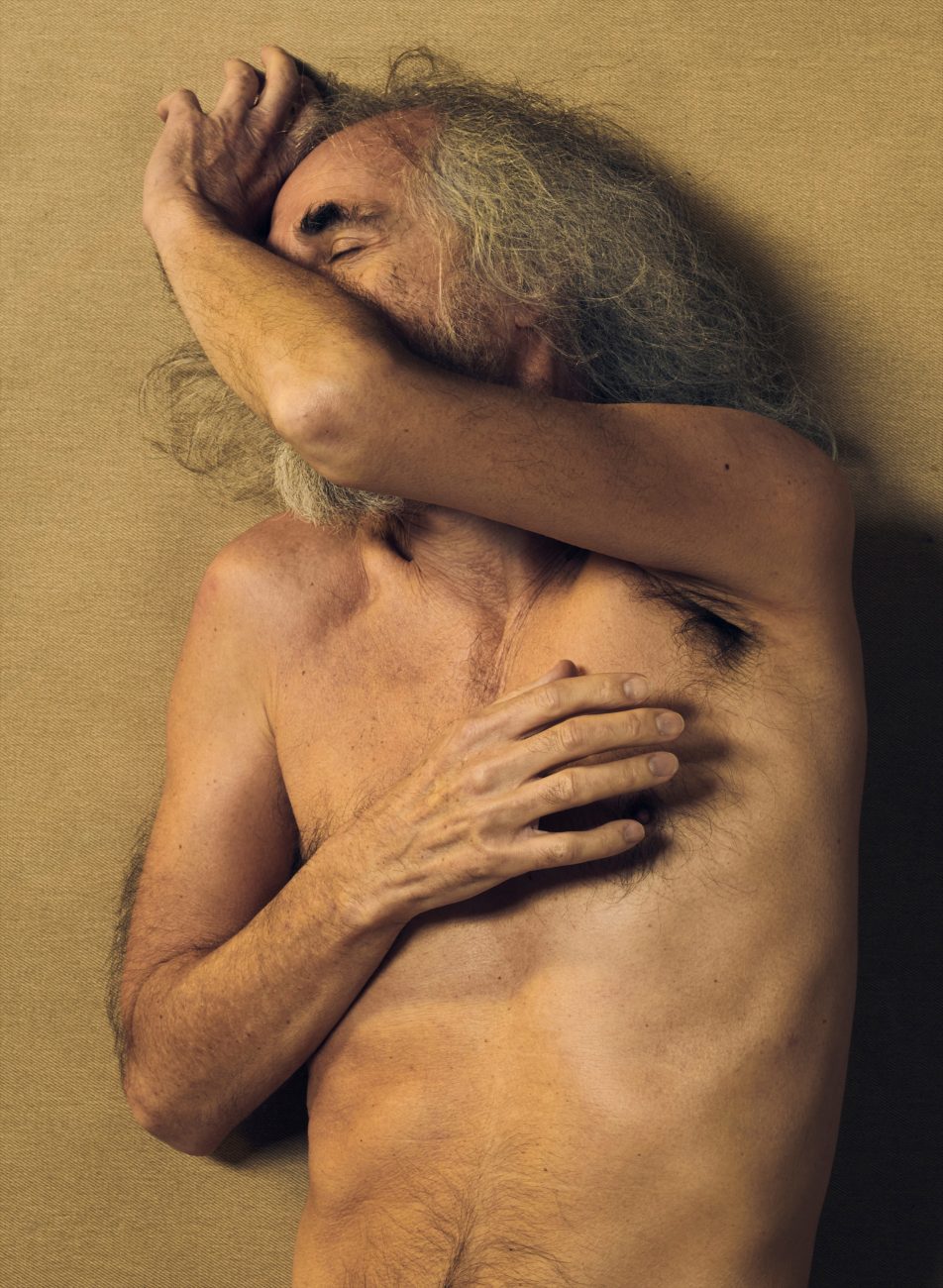

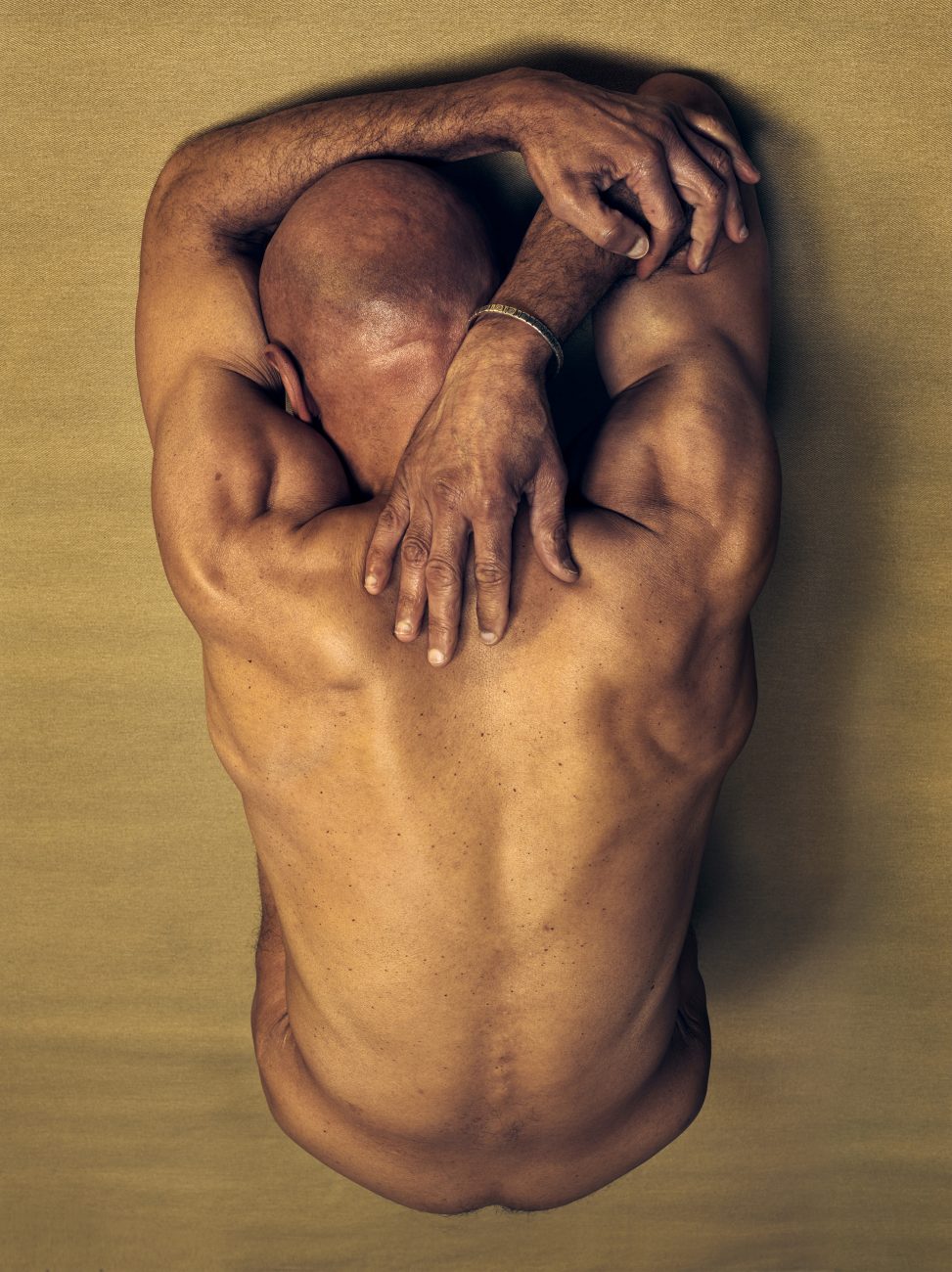

I light with gels and work with a reduced colour pallet. In a series like this it brings the flesh tones in line with no great jumps of colour; the variation is only tonal. Every one of these choices is made to help create a mirror that reflects the viewer. I like the bodies because they are imperfect, I like the roughness of the skin, the blemishes on the back, the wire-like hair. It's important to me the bodies in the images are of the people you pass in the street every day, a brother, a father, a son, a lover.

I had control when I wanted it, guiding, pausing to capture. But what this meant, I found, is that the unguarded moments revealed more than any calculated pose. Who is the main character in the story, the photographer or the subject, who controls the narrative? I wondered. I became familiar with the sitters, but had no urge to name each person, each character in this series. They told me their story, what they did for a living, why they modelled and why they responded to me, and their bodies told a different story again. Still, I chose to keep their faces obscured or cropped out of the image entirely, to represent a ‘universal’ male body instead of a particular identity.

Whether through blurring, veiling, obscuring or motion, the shift in focus from the face of the subject to the form constructs a new relationship between subject and spectator, the bodies become the site of the viewer’s self — as much projection as fact, perhaps more. (But isn’t that true of all interactions?)

We understand ourselves in part by recognising the ways in which we are similar to and different from others. I find in the bodies reflections of my own (strange that you need someone else to tell you what your body is doing). What is it to live in a man’s body; what it is worth? What does ‘worth’ mean, anyway, in the increasingly digital world of liking, linking, and sharing?

I read that people prefer their mirror image over their actual image, or how they look in photographs, because they are more familiar with the reflected version, something that is explained by something called the ‘mere-exposure effect’.

What we think we see in in a mirror is not the actual body but a distortion. We forget this about ten times a day, but it becomes clear when reflections obviously rearrange, distort or multiply the reflection, as they do in some of these images. This disjoint between reality and perception exists too in photographs of the body, where what we see is complicated by the representations we have seen before, and the preconceptions we bring with us. These photographs explore this relationship between the real and perceived truth. Just like our reflection in a mirror, it is separate from the physical self we inhabit. The still image, like our mirror reflection, allows us to explore a body, every small detail, every patch of skin and flesh. Without the returned gaze back making us uncomfortable, we are free to just stare, to take it all in.